Does subliminal advertising actually work?

ALAMY

ALAMYHidden messages that promote products in films once caused a moral panic. But is the much-feared technique really effective? The BBC's Phil Tinline helped devise an experiment to find out.

On 12 September, 1957, at a studio in New York, a market researcher in the Mad Men mould called a press conference.

James Vicary astonished the assembled reporters by announcing that he'd repeatedly flashed the slogans "Drink Coca-Cola" and "Eat popcorn" throughout a movie, too fast for conscious perception. As a result, he claimed, sales of popcorn had risen 18.1% - and Coke by 57.7%. This, he declared, was "subliminal advertising".

Vicary thought his fellow Americans would cheer this prospect - annoying cinema and TV ads could now be replaced with his imperceptible flashes. But on both sides of the Atlantic, his announcement sparked fear and outrage. "Welcome," cried one American magazine, "to 1984."

His story took a more serious blow when the manager of the cinema involved told Motion Picture Daily that the experiment had had no impact. In 1962, Vicary finally confessed that he hadn't done enough research to go public and that he regretted the whole thing.

OTHER

OTHERBut a nagging anxiety about the supposed power of subliminal advertising has never gone away. Ever since the 1957 panic, it has been banned in the UK. So is all this anything more than a hangover from sci-fi-style Cold War worries about mass brainwashing?

Psychologists have long agreed that flashing words too quickly for the conscious mind to register can have some limited effects in the lab.

And at the University of Utrecht in 2006, a team of experimental social psychologists, Johan Karremans, Jasper Claus and Wolfgang Stroebe, did manage to make subliminal advertising itself work - in strict laboratory conditions, provided a series of limiting factors are in place.

Their work suggested that subliminal advertising was only effective with products that people knew of and somewhat liked. The flashes made the brand name more '"cognitively accessible", their theory went, so it wouldn't work with very high-profile brands - you couldn't make a brand like Coca-Cola much more familiar to people than it already is.

They replicated their results, and published their findings in the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology.

But the crucial question, raised by Vicary's dubious claims, and never finally settled, is this - can you take all this out of the lab, beyond its strict controls, and reproduce it in the messiness of real life, on a mass scale?

Working under the guidance of Stroebe, I devised an experiment in which 98 participants volunteered to take part. Stroebe and his colleagues' research suggested that if you knew subliminal advertising is at work, it was ineffective, so it was only afterwards that what was being tested was revealed.No-one, apparently, has attempted this since the 1950s. So, as part of a BBC Radio 4 documentary, we decided to carry out a public test.

Also, the Dutch research indicated that advertising a specific drink brand with subliminal flashes was only effective if the audience actually wanted a drink. So it had to be a brand that was perceived as thirst-quenching.

So a pre-test survey was conducted to find a drink brand that might work. As with Stroebe's pre-test, the responses suggested that Lipton Iced Tea fitted the bill.

When the volunteers arrived, they were given crisps in an attempt to make them thirsty. They were sat in a theatre and divided into two groups, half with red blindfolds and half with black.

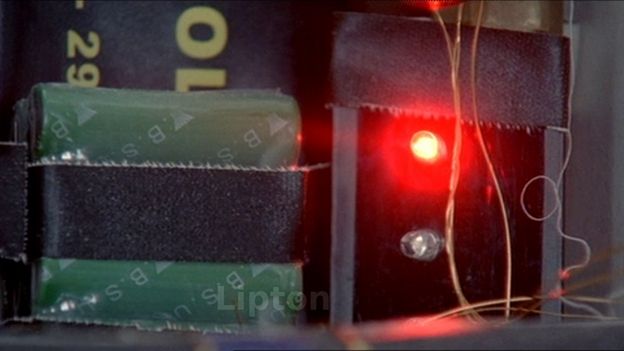

They were shown the same three-minute clip from the BBC/Kudos drama Spooks twice, but each time one group wore the blindfolds. The clip watched by the group with red blindfolds contained a 10-millisecond flash, every five seconds, of the word "Lipton", using a technique developed by BBC Research and Development

The participants, members of the audience of Radio 4's science show The Infinite Monkey Cage, were then offered a choice of two drinks - Lipton Iced Tea or a brand of mineral water - and asked to complete a questionnaire.

Strikingly, there was no significant effect.

For all participants, a few more people in the test group picked Lipton, but not enough to be statistically significant. When we removed those likely to have been immune to the subliminals - ie those who would have picked Lipton anyway, and those who dislike it and would never pick it, slightly more people in the control group picked Lipton, but this difference was not significant either.

The Test

- The test group watched a clip which included subliminal flashes of the word Lipton

- The control group watched a clip without any flashes

- The participants were then asked whether they wanted to drink Lipton iced tea or mineral water

- Test group (all participants): 46% chose Lipton, 54% water

- Control group (all participants) 37% Lipton, 63% water

- Results refined to exclude those who would definitely have chosen Lipton, or who would definitely not have chosen it

- Test group (refined) 53% Lipton, 47% water

- Control group (refined) 61% Lipton, 39% water

- Experts agreed the differences were not statistically significant

Given that we know this does work in the lab, there are many possible reasons why there wasn't a significant result in the public version.

Despite the crisps, a substantial number of the participants said they weren't thirsty. Maybe people didn't see enough of the flashes. Maybe the clip was too short, or not positive enough. Maybe a brief shot of someone drinking water had a counter-influence. Maybe it would have worked better with another brand. And maybe a larger sample was needed than was possible in the situation.

Or perhaps it was the subliminals themselves. Even if everything else is in place, getting the timing of the flashes right is very tricky.

If they are too fast, they are not even subconsciously perceptible. If they are too slow, some people would notice them - which would be disastrous for any advertiser trying this for real.

The experiment also suggested that stringing subliminals across an entire movie would be very laborious. The clip from Spooks was picked because it is full of fast cuts and moving camerawork. This, Stroebe advised, would help mask the subliminals, making them less consciously detectable.

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGESBut over the course of a whole film, the speed and transparency of the subliminals would probably have to be varied widely to make sure the audience didn't spot them. The most viable strategy would be to insert them only in the last few minutes before the end.

So this experiment did not finally disprove the notion that subliminal advertising could theoretically work in public.

But what it did demonstrate is that, while the fear of subliminal advertising may be based on a kernel of scientific truth, in practice this would be a devilishly tricky thing to pull off.

If, after months of preparation, with willing volunteers, with the distribution of crisps to induce thirst, we still couldn't achieve a result, the chances of achieving anything on a mass scale don't appear very attractive.

Furthermore, even if the subliminals had influenced choice immediately after the film, it is very doubtful that there would be a lasting effect on their drink purchases after they left the cinema.

And balance the low chance of success against the catastrophic PR (and legal) risk of getting caught doing this, and you'd have to be a true Mad Man to try it.